A Portable Paradise

by Pedro Cuperman

catalog published by Rena Bransten Gallery, 1988

and published in Stedelijk Museum catalog, 1990, as "Becoming Baroque"

Oh make me a mask and a wall . . . to shut off your spies

“In an age of traditional conformity,” wrote E.G. Lewis in Dylan Thomas: The Legend and the Poet, quoted by Mario Praz, El Pacto con la Serpiente, “the young poet would have at hand a set of conventional themes that he would certainly modify but that would nevertheless ensure continuity with his predecessors, and provide for adequate communication with his reader. In the past, such themes were indicated by ancient mythology, the Bible story or the legends of the heroes. In a revolutionary period such as ours, not only are values questioned, but conventions are discredited; so that the poet is thrown back upon his own inventiveness . . . for the creation of any theme at all.” In writing about Izhar Patkin’s The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden, I propose to take this opposition between imagination and convention as my starting point. Perhaps because in this Rose Garden, the individual, (as Nietzsche would say), wishes to contemplate itself mirrored by its conventions and by transfiguration of those conventions. Perhaps because, like some of its models, this Garden draws into the closed reality of myth and visible tradition, the open gaze of desire. “How else,” to quote the poet Rumi, “could a rose garden grow out of the dust?”

Each of the subjects inside the Garden can submit to various levels of reading. They organize the rhetorics of the Garden and structure its meanings: coins of exchange in a golden mirror; dialogue between signs open to dialogue through time and space. Only this atemporal, anonymous use of the pictorial sign unveils their ritual aspect without making it conventional, repetitious, redundant. The already known – is presented again, this time as an offering: a coin of desire in the palm of your hand.

|

Stefano da Zevio

Madonna of the Rose Garden, ca. 1402

Museo di Castelvecchio Verona |

A clear example could be the metaphorical structure that guides Patkin’s inventiveness. He does not start, like an abstract expressionist, from inner life; instead, he draws out of the past, and rejuvenates a symbol already exhausted in the late Middle ages. I refer to Stefano da Zevio’s Madonna of The Rose Garden, (ca. 1402), a gothic recreation of Paradise on earth inspired by a Persian miniature. Hortus Conclusus was the name of this enclosure; in it, the Virgin and the Christ Child occupy the center, surrounded by all the conventions and embellishments of gothic sentiment and ornamentation. As the spectator will see, the painter has retained the Garden, but its inhabitants were replaced. Not exactly a parody – even if he avails himself of that language – because parody, in principle, is an ironic, invasive reading that unmasks one text with another, whereas Patkin reads Da Zevio’s work as one would read a dictionary. What had its beginnings in parody turned out to be a classic baroque operation, in the sense of extracting from identical visual forms different or opposite meaning. Durell speaks of one of his characters as someone who is capable of “this weird translation of feelings into gestures which belied words and words which belied gestures.” For his inspiration, Da Zevio goes to a Persian miniature, Patkin goes to Da Zevio, and both to the Garden as a sign for what apparently is a universal archetype. The Garden as a visual form precedes them; and so does the myth of Paradise.

But what is paradise in The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden? At first sight it appears that the space, the space of contemporary art, is peopled not by solemn symbols but by signs, faceless icons, clichés out of a dictionary, and like the world from which they are drawn and towards which they are eventually destined, they cannot exist unless they are seen or used by somebody. But, precisely, this availability, this facelessness, is what language is: a vacancy that waits to be occupied and used in the Saussurean sense of parole.

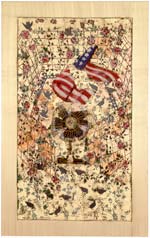

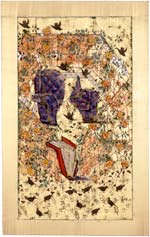

An American flag, Pride, occupies the same central space as an electric fan. Both face each other. Out of that montage, alternative meanings are touched off: in the wind and out of the wind. In another painting, Comfort, an armchair and a half-opened book ask to be seen as a metaphor of reading. The moving gaze will follow.

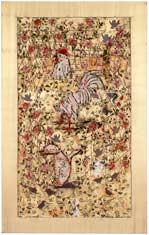

The internal or external dialogue must proceed. I see the painting with the cock and the teapot, Tradition, and start thinking about the language of desire and the codes of psychoanalysis that go with it: a vaginal sacrifice, coitus and birth, or vice-versa; the forbidden . . . . But Patkin does not allow me the pleasures of interpretation. As if fearing reduction he seeks refuge in the fragile exchange of ‘ready-mades’: “the whole world rests on chicken wings,” he tells me, quoting a Hebrew proverb.

I have said that Patkin’s language is not specifically that of parody. His quotations, his copies, his objects do not seek to take revenge on art. His reproductions are above all an ironic reference to the by now exhausted, post-modernist brawls with originality and truth. Signs can hide what goes without saying, or say it again; but a girl’s dress, a handy umbrella, a clock, these undistinguished symbols, seem to be asking for something else. If looking at them is not enough, should we not touch them?

Those paintings have a way of behaving, of taking and bringing . . . paradise wrapped in a bonbonniére. Take it. That is, take me.

What matters is not the presence or absence of symbols, but the fact that new forms are established. New forms of communication and possession between each of the texts, and with the spectator.

Through the golden frame we enter the Garden (closed but open for us), where the birds are waiting. A baroque picnic on our journey to Ithaca; and “it is better to let it last for long years.” A place where we can be, where we can see, where there will be an exchange. A place where we have been invited to a dialogue that takes place as play and possession.

To speak of possessing a work of art is a paradox. Hegel believed that our being is a struggle between the finite and the infinite. And one of the greatest paradoxes of being is that one can think the infinite but, still, one faces continually his own finitude. Thinking and possession are incompatible. Possible but incompatible. The Unhappy Consciousness recognizes its limits, but imagination is insistent and rebels. As if in illustration and defiance of this disconsolate contradiction, Patkin has created an oxymoron in space: The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden, a Garden that is closed and open, that invites us to see and see ourselves as if offering us the only possibility left: that of seizing a last breath of Paradise.

Translated with the assistance of Lydia Hunt

|

( click images for larger view)  |

|

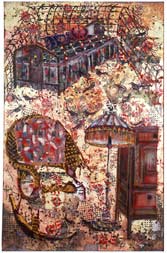

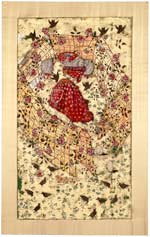

The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden,

1985

73” x 49” oil, leaf, screen

private collection |

|

|

|

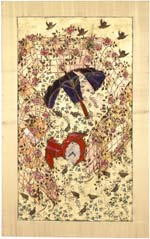

The Perfect Existence in the Rose

Garden: Insurance, 1988

64” x 40” oil, leaf, screen

The Contemporary Museum,

Honolulu, Hawaii

|

The Perfect Existence in the Rose

Garden: Pride, 1988

64” x 40” oil, leaf, screen

private collection |

|

|

The Perfect Existence in the Rose

Garden: Comfort, 1988

64” x 40” oil, leaf, screen

private collection

|

The Perfect Existence in the Rose

Garden: Confirmation, 1988

64” x 40” oil, leaf, screen

collection of the artist |

|

|

The Perfect Existence in the Rose

Garden: Tradition, 1988

64” x 40” oil, leaf, screen

private collection

|

|

|

|

|

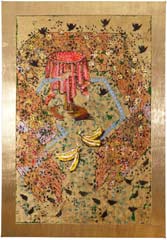

The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden: Evolution, 1988

72” x 50” oil, leaf, screen

private collection |

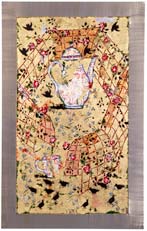

The Perfect Existence in the Rose Garden: High Tea, 1991

64” x 40” oil, leaf, screen

private collection |

|

|